Where Do We Go From Here?

Was wholesale integration a mistake for the black community?

Today, well over 50 years removed from the height of the Civil Rights Movement, it may be hard for us to imagine the choices that our black foreparents faced back then and for the decades and centuries before. One foundational issue that they faced was that of integration. Removing the legal and social barriers that kept blacks from advancing in this country was one of the main goals of the Civil Rights Movement.

Many of those legal barriers have indeed been removed, and many blacks have successfully “integrated” into mainstream America. However, there still exists a significant number of blacks who have not been able to successfully integrate into America and all that it has to offer, which begs the question in hindsight, was wholesale integration the right strategy? Did an integration strategy forsake the development of a strong independent and interdependent black community with its own viable institutions?

This is the first in a series of articles where I will explore those two questions in detail. In this article I will start with Dr. King’s approach. While most will remember him as a staunch integrationist, towards the end of his life, his views had shifted. In his 1967 speech, “Where Do We Go From Here,” King begged a prophetic question that still plagues not only black folks in this country, but the country as a whole.

Revisiting this speech 56 years later in 2023, one thing that stuck out to me was the extent to which Dr. King was heavily involved in institution building for blacks. He wasn’t merely interested in getting legislation passed (though he did much to do that as well). His brand of social justice was giving blacks an equal opportunity for their communities and businesses to be able to thrive in an integrated environment where the decades of segregation had left them at a massive disadvantage in terms of visibility, connections to the wider society and the resources to be on par with their white counterparts.

Dr. King framed black communities across the country as “domestic colonies” that were designed for exploitation and were not made to be sustainable on their own, as colonies tend to be. Once the connection the imperial center of whiteness was severed, with the ending of legal segregation, these colonies were left to fend for themselves without any ability to produce anything for themselves. This would be the fate of many former colonies across the twentieth century once they were given their nominal independence. They were independent from the outright exploitation of the empire, but functionally these areas were still dependent upon the systems of exploitation that functioned as cords of life support. Enough to keep them alive but not enough for them to thrive. Given the anti-imperial direction Dr. King would take just a year later in 1968, this colonial comparison was not merely incidental.

In opening of Where Do We Go From Here, Dr. King lays out all the areas of successes within the Civil Rights movement, moving from the mainstream successes of the integration of the schools to the many social programs that he and other groups had been a part of. The areas of life where Dr. King fought for social justice go well beyond the conventional understanding of segregation. Because it pervaded all aspects of life, in the North and the South, Dr. King was especially drawn to the often neglected aspects of life.

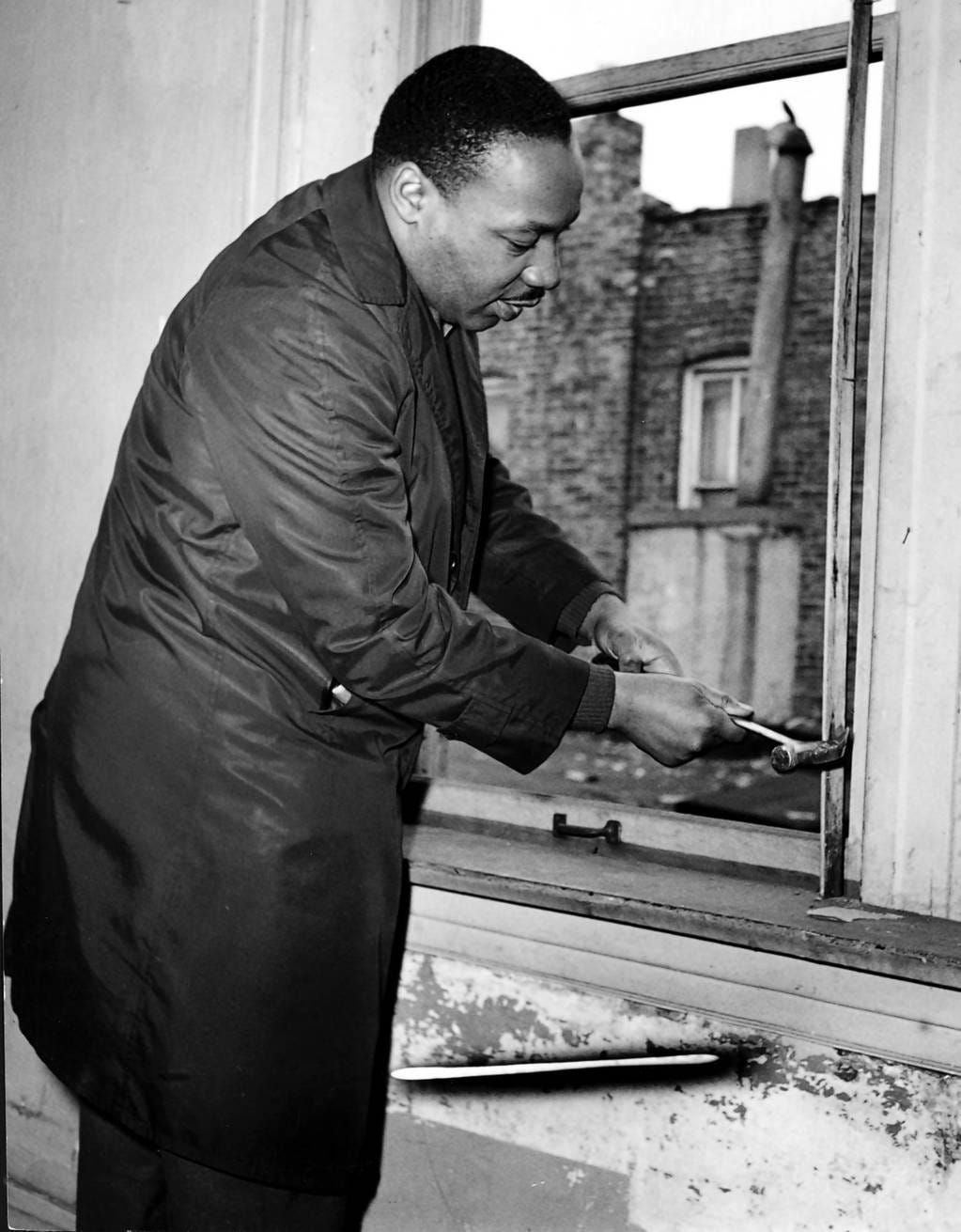

He described an adult education program called the “Citizenship Education Program” which trained people in literacy, consumer education, planned parenthood, among many other things. This program was able to be replicated in ten southern states. In Chicago he and his allies conducted “open housing” marches which challenged the very power structure of segregation to which their demands were met by the city. They began a housing rehabilitation project which renovated deteriorating buildings and gave the tenants an opportunity to own their homes.

Most striking was “Operation Breadbasket” which was originally launched by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Atlanta in 1962, which Dr. King and the SCLC brought to Chicago in 1966. According to Dr. King, the premise of the program was to boycott business which denied blacks “jobs, advancement, or plain courtesy”. Operation Breadbasket was a wide reaching initiative aimed at the economic rehabilitation and advancement of not just black individuals but black communities. It had a simple ethos:

“And so Operation Breadbasket has a very simple program, but a powerful one. It simply says, ‘If you respect my dollar, you must respect my person.’ It simply says that we will no longer spend our money where we can not get substantial jobs.”

This ethos was not just limited to fair hiring practices by white owned businesses though. It also focused on fair opportunities for black owned businesses and services. Even something as trivial as garbage collecting was an aspect of life where whites had an unfair advantage in competition.

Whites controlled even the garbage of Negroes. Consequently, the chain stores agreed to contract with Negro scavengers to service at least the stores in Negro areas. Negro insect and rodent exterminators, as well as janitorial services, were likewise excluded from major contracts with chain stores.

Not only did those chain stores capitulate, they also agreed to advertise in black owned newspapers stands in black communities, something rarely done. This aspect of segregation was far reaching. Because of these types of practices, black contractors from painters to masons, electricians, excavators were forced into being small business by the enforced monopoly of white contractors. Breaking this monopoly, as Operation Breadbasket was designed for, was vital for the wellbeing of the neighborhood. By the time of this speech, Breadbasket had brought twenty-five millions dollars of new income annually into black communities.

For me, as someone that has grown up in what many of us had believed to be Dr. King’s vision of America, it was peculiar for me to imagine him spending so much time working with helping garbage collectors get contracts with the white stores that had been excluded from collecting from for decades. Especially today the idea of celebrating a black owned garbage collecting service would sound more like an unfunny joke than anything. This was the extent though to which inequality needed to be remedied following the years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That year was not a culmination of decades of work, but a starting point. Blacks were now equal in the eyes of the law. From there, the work was needed to be done to to erase the scars from the shackles of Jim Crow and transition black communities into their newfound equality.

This brings us to the ultimate question at hand that Dr. King was begging all the way back in 1967: Where do we go from here? Despite the veritable gains of the civil rights movement, there was still more to be done. By 1967 he described the situation as dire among black communities all across the country that were sinking deeper into poverty. Despite the fact blacks were now considered to be a full person in law, in function they are only half a person:

“Today another curious formula seems to declare he is fifty percent of a person. Of the good things in life, the Negro has approximately one half those of whites. Of the bad things of life, he has twice those of whites. Thus, half of all Negroes live in substandard housing. And Negroes have half the income of whites. When we turn to the negative experiences of life, the Negro has a double share: There are twice as many unemployed; the rate of infant mortality among Negroes is double that of whites; and there are twice as many Negroes dying in Vietnam as whites in proportion to their size in the population.”

He goes on for another few minutes listing the areas in which blacks were facing massive inequality, by the very nature of them living in these “domestic colonies”. Even the very quirks of colloquialisms in English language, from the associations of pureness and chastity with whiteness, and degeneracy and darkness with the color black seemed to instill in blacks a feeling of inferiority. Black people were being assailed on a daily basis by a white supremacy which was as natural as the air we breathe, deeply ingrained in our society.

Listening to this speech from the vantage point of 2023 we have seen blacks reach the “promised land” only to find out that the promises of riches and abundance that we had been inculcated with from the days of slavery onward, turned out to be a little “white lie” of its own. Of all the things Dr. King described of the condition of black people in 1967, almost every single one of those things could be said to be true of blacks today. So this brings us to the question once again: Where do we go from here?

69 years after segregation was brought down in our school systems, 59 years after the great victory of the Civil Rights Act, what of substance has wholesale integration brought black people? The very reason that the celebration of black owned garbage collecting businesses sounds strange to our ears today is the very source of the problem. We have brought down the barriers of segregation and made illegal the colonial exploitation sanctioned by the imperial center, but like many former European colonies across the world, the abandonment of our “domestic colonies”, leaving them to their own devices is as much of a crime as we have become accustomed to blaming countries like France with its intentional impoverishment of its former colonies in West Africa.

But not only have we abandoned them, we have set up our own pipelines of exploitation and extraction that is no longer based upon the laws of Jim Crow but now the laws of economics and opportunity. Think of the number of people you know who have made it out the “ghetto” from the 1970s onward, be it middle class families that moved to greener pastures in suburban communities, or athletes who were given all the resources to succeed by youth and high school sports programs such as basketball or football. For every person that has “made it out” there are countless others that are regarded as if they are toiling away in some twisted purgatory waiting their turn in advancement.

Today we celebrate advancement by the individual. We love to celebrate “black excellence”. We celebrate the accomplishments of athletes and entertainers. We love to celebrate epithet of the “first black” to accomplish something or sit in a position in which blacks have not sat previously. But where is the regard for those communities we’ve left behind? Like countries such as Chad, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Gabon, and Niger, they are out of sight and out of mind until some tragedy afflicts them or they take measures into their own hands, often militantly to disrupt these new pipelines of extraction and exploitation set up to siphon out whatever value is found. It is time for us to regard “black excellence” not just by the individual, but by our condition as a whole. We should want to be a people in excellent condition.

Just as is necessary for a newly independent nation, we as a people needed more initiatives such as Operation Breadbasket that was focused on institution building for black communities to give them the tools and resources to thrive in an integrated America. I challenge you to imagine what kind of country we could be living in, if programs like Operation Breadbasket had made it to cities beyond Atlanta and Chicago in the 1960s. Imagine an Operation Breadbasket in every impoverished black neighborhood across the country. Would there have been the cries of despair manifested in the riots in Los Angeles in 1992? Would we have been able to weather the storm of the economic crash of 2008 and rebound back in the resultant years? Would we have to constantly remind our society with chants of “black lives matter” for the past decade and a half or would our condition and general wellbeing have been self-evident enough for people to understand this? Imagine the progress that could have been made from such initiatives over the course of the last 60 years.

As I write in 2023, just as Dr. King had spoken in 1967, I ask the same question, but with a very different tone: Where do we go from here? How can we begin to build upon the vision of Dr. King and the many other civil rights activists who allied themselves with him? How can we begin to “build back better” black institutions that have essentially been eviscerated in the years following integration? Can we sever the post-colonial pipelines that have further depleted our neighborhoods?

Operation Breadbasket was to be the first of many projects that Dr. King had envisioned across the country.

“This is the first project of a proposed southwide Housing Development Corporation which we hope to develop in conjunction with SCLC, and through this corporation we hope to build housing from Mississippi to North Carolina using Negro workmen, Negro architects, Negro attorneys, and Negro financial institutions throughout. And it is our feeling that in the next two or three years, we can build right here in the South forty million dollars worth of new housing for Negroes, and with millions and millions of dollars in income coming to the Negro community.”

If we are to truly bring into reality Dr. King’s dream, we need not only celebrate black excellence” when it comes to athletes, entertainers, and politicians. We need to see black excellence in the black workmen, architects, attorneys and garbage collectors. We need to create a society where black financial institutions created for the advancement of black interests can be a reality. We need to bring the billions and billions of dollars that are generated by black people as a whole, and invest it into the neighborhoods we have all but abandoned.

At the end of his speech Dr. King triumphantly ends with echoes of the gospel song and civil rights protest anthem, “We Shall Overcome”:

“This is our hope for the future, and with this faith we will be able to sing in some not too distant tomorrow, with a cosmic past tense, ‘We have overcome! We have overcome! Deep in my heart, I did believe we would overcome.’”

Just as Dr. King triumphantly stated, I want to see that “not too distant tomorrow” where we too can triumphantly declare that “we have overcome” our hurdles today.

Great piece, young Sir!

Thanks for your excellent write-up on the causes of our economic plight and the solutions!